Patents and Trademarks

Nishimura & Asahi / Japan

The legal framework for patents and trademarks in Japanese Pharma. Prepared in association with Nishimura & Asahi, a leading law firm in Japan, this is an extract from The Pharma Legal Handbook: Japan, available to purchase here for GBP 149.

1. What are the basic requirements to obtain patent and trademark protection?

The Patent Act states that an invention must be novel, non-obvious, and have industrial applicability. The Trademark Act allows registration of any trademark unless the mark is the same as or similar to another registered mark or otherwise prohibited under the Act. On top of the Trademark Act restrictions, there is a special restriction for medicine to avoid confusion among medicines.

2. What agencies or bodies regulate patents and trademarks?

The Japan Patent Office (the “JPO”) regulates both patents and trademarks.

3. What products, substances, and processes can be protected by patents or trademarks and what types cannot be protected?

For patents, basically any novel, non-obvious substances and processes with industrial applications can be protected. However, under the Japanese Patent Act, medical treatments and related practices are not approved for patents. In general, no patents can be granted for any method of operating on, treating, or diagnosing human bodies. This regulation is similar to Article 53(c) of the European Patent Convention. Although this regulation had been controversial, especially with regard to regenerative medicine technologies and gene therapy, a revision to the relevant guideline in 2003 made some of those technologies distinct from medical treatments and subject to patenting. However, it is worth noting that regenerative medicine technologies and gene therapy are also problematic from a moral perspective (public order and decency). For instance, a technology to create human embryonic stem cells has the former issue, while a genome editing technology (such as CRISPR-Cas9) applied to germ cells (including fertilised human embryos) has implications for the latter. Discussion of these points have intensified in recent years (see a parallel discussion in Article 53(a) of the European Patent Convention).

In the trademark area, the name of a medicine that would create consumer confusion with regard to other medicines will not be approved, even if a trademark on the name is granted under the Trademark Act.

4. How can patents and trademarks be revoked?

Any interested party may make a claim for invalidation of patents or trademarks via a request to the JPO. The JPO will decide whether or not a patent or a trademark should be revoked, as the evaluator in the first instance. The second instance evaluator of an invalidation request is the Intellectual Property High Court of Japan, which is a branch of the Tokyo High Court. If the litigants are unsatisfied with that judgement, they can appeal to the Supreme Court of Japan.

5. Are foreign patents and trademarks recognized and under what circumstances?

No such recognition is granted.

A foreign patent applicant can submit an international application to its home country under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (the “PCT”) and can include Japan as one of the target countries in that application. However, even in such cases, whether a patent will be granted for the relevant invention ultimately is left to the discretion of the JPO, after a substantive examination. Apart from the PCT and the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (which is a fundamental treaty for industrial property), Japan is neither a member of any international patent application system (e.g., European patent under the European Patent Convention) nor a member of any unified international patent framework (e.g., European patent with unitary effect under the Regulation (EU) No 1257/2012).

6. Are there any non-patent/trademark barriers to competition to protect medicines or devices?

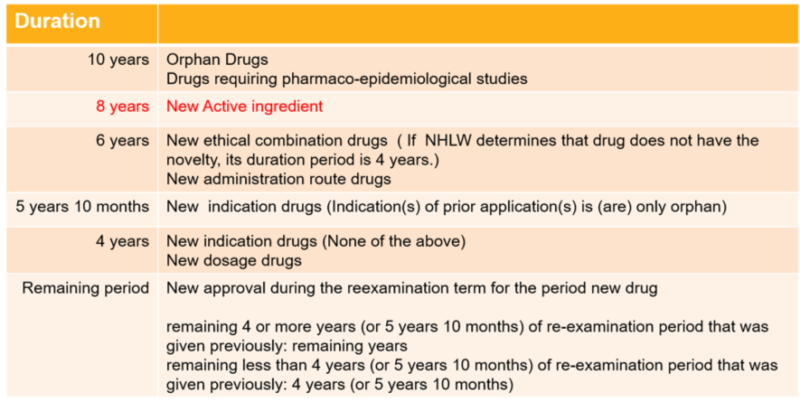

The PMD Act creates a Re-examination System, and provides for a certain Re-examination Period when a new medicine is approved, or in other cases set forth in the list below.

The Re-examination Period may be extended for a certain length of time, not to exceed ten years. The purpose of the Re-examination Period is to obtain safety and efficacy evidence in the real healthcare market. The MA holder must conduct research and trials pursuant to an agreement reached with the MHLW at the time of approval, including Post-Marketing Surveillance and gathering Drug Safety Information Data during the Re-examination Period. Then, after the relevant period, the MHLW will re-examine and approve the efficacy and safety of the medicine. Until the medicine is re-examined and approved, generic medicines cannot come into the market. In other words, in order to market generic medicines, it is a prerequisite that the Re-examination Period for the corresponding pioneer drug has been completed and that an evaluation of its efficacy and effectiveness has been established. Accordingly, the Re-examination Period works similar to Data Exclusivity in other jurisdictions.

7. Are there restrictions on the types of medicines or devices that can be granted patent and trademark protection?

No.

8. Must a patent or trademark license agreement with a foreign licensor be approved or accepted by any government or regulatory body?

No.